When Did Farm Animals Start Getting Vaccinated

four Vaccines and Vaccinations: Production Animals

- Describe risks and management factors to consider when vaccinating cattle, small ruminants, and swine

- Draw cause and clinical manifestations of conditions for which we vaccinate cattle, small ruminants, and swine

- Explicate where and how to vaccinate production animals

- Ascertain what is meant by commercial, autogenous, and on-farm vaccine production

- Create advisable vaccine protocols for cattle, small ruminants, and swine

*

Dairy Cattle

Dairy Cattle

Dairy and beef cattle generally always live in a herd. Management practices will therefore affect multiple animals. Likewise, from an infectious affliction standpoint, it has to exist kept in mind that not one, but multiple animals will exist exposed to a particular pathogen. As a result, the prevention of disease on dairy farms needs to be targeted towards groups of animals and the entire herd rather than individual animals. Disease prevention is crucial to permit the economic survival of the farm and to ensure brute welfare. Specific brands of vaccines volition non be discussed for beef or dairy cattle because there is tremendous variability in vaccines used. Examples of diseases for which cattle may exist vaccinated include bovine viral diarrhea (BVD), infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR), parainfluenza (PI3), bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV), leptospirosis, Pasteurella, Histophilus (Hemophilus), Campylobacter (Vibrio), and clostridial diseases. Specifics of vaccines and their employ will be covered in species-specific coursework later on in the curriculum. An example of which vaccines are used at which life stage is included in the department on beef cattle equally are descriptions of the diseases we protect confronting with vaccination in cattle.

Risks and Management Factors

The host has various defense mechanisms to preclude or to deal with infections. A given species or fauna might not be susceptible to a certain affliction. For example, Due east. coli O157:H7, a potentially fatal bacterium for humans, is a normal gut commensal for cattle. Cattle do not have the receptors for the toxins of this bacterium in their kidneys and so they cannot develop the hemolytic uremia syndrome that affects humans. Other defense mechanisms, specific and not-specific, are part of the immune organization. These defense force mechanisms may be impaired due to the animal's age, inadequate diet, and other stressors from within the brute, or may be impaired due to management practices. Stress due to heat, weaning, malnutrition, infection pressure level (corporeality of exposure to a given pathogen), transport, and other factors will negatively impact how the allowed system can react to a "pathogen attack".

Furthermore, an infectious disease tin can only spread through a population if the pathogen 'finds' susceptible animals to infect. Some animals might become sick, simply if a population (herd) has many resistant animals, the probability of new infections can be so low that the disease 'dies out' even if non all animals are resistant to the illness. This is called "herd immunity". In man medicine this principle is used every yr as we receive flu shots. The aim is to reduce the number of susceptible humans through flu vaccinations and so reduce the likelihood of new infections, particularly in children and immunocompromised people.

So for obvious reasons, the environs and management practices play a crucial role in disease prevention on subcontract by influencing the fauna and the pathogen. Whatsoever management practices that subtract the infection force per unit area on animals (for example, hygiene or biosecurity) will back up animals in coping with infection pressure and will reduce the likelihood that animals volition even become exposed to the pathogens.

Vaccination is only role of this puzzle and cannot be used as a standalone practice to forestall affliction or infection on farm. Vaccination is not a miracle intervention. It does not result in immediate immunity or resistance against diseases in all vaccinated animals. Starting time, it takes time for the immune system of the animal to react to the vaccine and second, just because an animal is vaccinated, information technology does not automatically mean that the animate being cannot be infected or develop the affliction. However, vaccination can be used every bit one of many management practices to aid animals cope with potential infection threats.

Vaccinating Production Animals

When thinking about vaccinating a dairy herd, you lot take to understand the production system and the diseases that are of importance for that item dairy farm. You demand to enquire several questions:

- What management practices are already in employ on this dairy farm and where could improvements possibly be fabricated to decrease infection pressure? Examples include improving hygiene, non bringing in animals from unknown sources, and limiting foot traffic between age groups.

- Which pathogens are of concern for their impact on the health and production of animals? If an animal is unlikely to ever meet a pathogen, it is probably not necessary (and is possibly too costly) to vaccinate against it. Do non over-vaccinate animals, and tailor the vaccine plan toward each herd individually.

- Practice benefits of a possible vaccination outweigh the costs of the disease or could vaccination be economically detrimental? For example, Foot-and-Mouth-Disease (FMD) has not been diagnosed in the Usa since the 1920s and the detection of positive antibody titers in animals would result in serious trade restrictions. Therefore, routine vaccination against FMD is probably not economically sound.

- When is the best time to vaccinate the animals? On farms, it is ever groups of animals, not individuals, that are vaccinated with a given vaccine. The timing of the vaccination has to take into account which age groups are at the highest risk for diseases, how long it takes for an creature to build up immunity, when the animals are going to be handled for any reason, and when the potential stressors occur in an brute's life. For example, when is the best fourth dimension to vaccinate a dairy moo-cow confronting pathogens associated with calfhood diarrhea? Calves desperately need to ingest the antibodies in the colostrum of its dam (passive immunization) to allow them to handle infections until they were able to build their ain immune response. The moo-cow needs several weeks after vaccination to develop significant antibody concentrations that can be deposited into colostrum. And then, keeping biology and direction practices in heed, in this example, it is best to vaccinate the dam in the weeks earlier calving and then the dam can evangelize these antibodies through the colostrum to the calf to gear up the dogie's immune system for a potential exposure in the get-go week of life.

- Read the label of the vaccines! What is the dosage and route for vaccine assistants? How long volition the immunity last? Some vaccines are for heifers only and some must not be given during pregnancy. Other vaccines (in particular those against zoonotic pathogens) are to be administered by the veterinarian merely. Additionally, you lot have to remember that yous are administering a biological drug to a food production animal. Therefore, you lot demand to consider withdrawal times to ensure safety of meat and milk from that animal every bit products from that beast may enter the human food chain. Withdrawal times may be based on the organism itself or on other components of the vaccine (for example, preservatives or adjuvants).

*

Beef Cattle

Beef Cattle

The role of vaccines in a preventative health plan for beef cattle is to preclude or eliminate clinical disease in an individual or a population of cattle. This is accomplished by decreasing the incidence and severity of illness through increased level of immunity as part of a preventive wellness program. No vaccine is 100% effective. Vaccines are part of a preventive health program that should include management procedures and handling, parasite control, and nutritional considerations that reflect an in-depth agreement of non only the beefiness product system but also farm-specific issues and goals.

Factors to Consider in Developing a Vaccination Strategy

When developing a vaccination strategy, several factors must be considered. Some of these factors are:

- Course of cattle (age)

- Nursing calves, weaned calves, yearling cattle, replacement heifers, pregnant cows, open cows, breeding bulls

- Production system the cattle are in

- Moo-cow-Calf, Stocker/Backgrounder, Feedlot

- Open organization (purchasing and bringing in cattle) vs. Closed system

- What to vaccinate for

- Reproductive Diseases

- Respiratory Diseases

- Systemic Diseases

- Goals of the producer / history

- Time to come plans, direction, etc.

- Previous challenges/approaches

- Adventure tolerance of the producer

- High vs. Low

- Expectations

- Facility availability / husbandry skills

- Ease of handling, stress of handling

- Labor needed/available

- Compliance ability

Vaccination does not equal immunization, then designing the vaccine programme also requires consideration of factors affecting immune response. These factors can include:

- Age of dogie

- The bovine's immune system begins to develop prior to birth but does non reach maximum responsiveness until subsequently in life.

- In improver there is thought to be "maternal interference" where passive immunity obtained through colostrum consumption may interfere with ability for immature calves to respond to some vaccines.

- Nutritional Status

- Current and previous nutritional status should be considered. Cattle that accept been scarce in key components (protein, energy, vitamins, and minerals) may have a decreased power to mount an allowed response.

- Stressors

- Vaccines should be administered at times of low or minimized stress and, if possible, prior to expected stressors. Common stressors include environmental temperature, affliction status, parasite load, transport, weaning, nutritional changes, handling, direction practices (castration, dehorning, etc), and comingling.

- Timing of vaccination

- The time between vaccination and challenge by infectious agents is important. If using a killed vaccine, you lot need adequate time for a booster dose when first administering.

- Additional considerations such as time post-obit parturition or prior to convenance, colostrum product, pregnancy condition, and avoiding stressors are of import as well.

- Endeavour to incorporate vaccination with other herd management procedures when possible to take full advantage of handling efficiencies; your goal is to minimize frequency of handling, which is a stressor.

Recommended Vaccination Schedules

Preventive health programs for beef cattle in the upper Midwest provide recommendations for vaccines at specific lifestages.

| LIFESTAGE | RECOMMENDED VACCINE |  |

| Birth |

| |

| Branding (mid summer) or Prebreeding |

| |

| Preweaning |

| |

| Weaning |

| |

| At entry to feedlot (Variable; based on vaccine history and risk class) |

| |

| Revaccination (Variable; based on vaccine history and chance course) |

|

| LIFESTAGE | RECOMMENDED VACCINES |  |

|---|---|---|

| Prebreeding 1 (viii-10 months) |

| |

| Prebreeding two (xxx days before breeding) |

| |

| Precalving 1 if on a fall (significant cow) vaccine schedule |

| |

| Precalving 2 (5-7 weeks precalving) |

| |

| Motility to cow schedule |

| LIFESTAGE | RECOMMENDED VACCINES |  |

| Fall Pregnancy Bank check or Prebreeding |

| |

| Precalving (3-7 weeks precalving) |

|

Vaccination Risks and Methods

As in modest animals, side-effects can occur with vaccination in cattle. These include soreness/swelling/knots at the injection site, fever, off-feed, and potentially anaphylaxis (allergic reactions). "Endotoxin stacking," the human action of giving multiple killed bacterin vaccines (frequently Gram negative or Gram negative-similar) vaccines together, has been associated with college incidence of agin reactions, failed immune response, and death.To minimize vaccine risks:

- Avoid the assistants of more than two killed bacterin vaccines at the same fourth dimension

- Do not milk shake killed bacterial vaccine such as clostridial (blackness-leg) products

- Never vaccinate on days where cattle are heat stressed

- Store vaccines properly

- 35-45oF, DO Non FREEZE, and avert sunlight

- Administer with proper care

- But employ licensed, quality vaccines

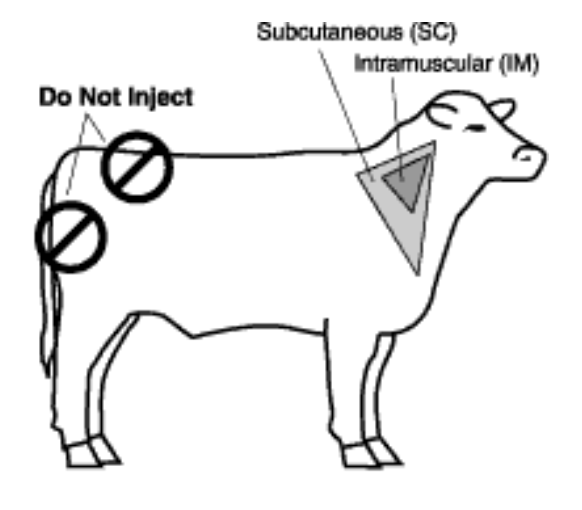

Beef Quality Balls Vaccination Administration Guidelines

Any injection has the ability to crusade a detectable lesion at slaughter. Beef Quality Assurance programs offer guidelines in proper administration of injectable products with the goal of maintaining and increasing the quality of the end product.Some full general recommendations include:

- Use vaccines labeled for subcutaneous road of administration whenever possible.

- Administer all vaccines in the neck region.

- Inject in a clean site.

- Replace needles frequently or use single apply needles.

- Apply an appropriately sized needle for the intended injection route.

- Employ good sanitation when withdrawing vaccines.

- Use properly cleaned and maintained syringes.

| Subcutaneous (SC) (1/2 to iii/4 inch needle*) | Intravenous (IV) (ane i/two inch needle*) | Intramuscular (IM) (i to 1 1/2 inch needle*) | |||||||

| Cattle Weight (lbs) | <300 | 300-700 | >700 | <300 | 300-700 | >700 | <300 | 300-700 | >700 |

| Estimate needle required for thin injectable viscosity (ex: saline) | xviii | 18-xvi | 16 | xviii-16 | 16 | 16-14 | 20-18 | 18-16 | 18-16 |

| Gauge needle required for thick injectable viscosity (ex: oxytetracycline) | eighteen-16 | 18-sixteen | 16 | 16 | xvi-14 | 16-14 | 18 | 16 | 16 |

*Select the needle to fit the cattle size (the smallest practical size without bending)

—"Recommended needle size", https://bqa.unl.edu/bqanebr-article-three

Diseases to Vaccinate Against in Beef and Dairy Cattle

Diseases in beef and dairy cattle to vaccinate confronting, include:

- Bovine viral diarrhea (BVD)

- Infectious bovine rhinotracheitis (IBR)

- Parainfluenza (PI3)

- Bovine respiratory disease circuitous

- Leptospirosis

- Campylobacter

- Clostridial diseases

- Brucellosis

Bovine Viral Diarrhea

BVD is a common cause of respiratory and reproductive issues in the herd. Information technology is an economically important disease in many countries. The disease is caused by the bovine viral diarrhea virus, which may cause chief disease or exist function of a large circuitous of infections. Cows infected during pregnancy may abort, give birth to a stillborn dogie, or give birth to a live calf. Calves can be infected in utero or after birth. Calves born carrying BVD virus will never clear the infection and will shed the virus continuously into the farm surround. Signs of BVD in adults are highly variable and include fever, lethargy, loss of appetite, ocular discharge, nasal discharge, diarrhea, and decreased milk product. Infected calves may have cerebellar hypoplasia; signs of this are ataxia, tremors, a wide stance, and failure to nurse.

Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis

IBR is a highly contagious, infectious respiratory disease that is caused by bovine herpesvirus I. It can affect immature and older cattle. IBR causes astute inflammation of the respiratory tract; clinical signs include those of respiratory illness (mucosal hyperemia, erosive mucosal lesions, nasal discharge, coughing), and also conjunctivitis, abortion, and encephalitis. After the first infection, the virus is sequestered in neurons in the brain as a latent infection. At times of stress, the virus undergoes recrudescence and can be shed from the eyes and nose. Because an infected animal never clears the virus, animals that are seropositive for bovine herpesvirus one cannot be shipped into countries that are free of the disease and cannot be housed in artificial insemination (AI) centers. Carrier cattle should be identified and removed from the herd.

Parainfluenza

The PI3 virus infects the upper respiratory mucosa, where it is shed in aerosols (sneezing and coughing) and by straight contact. PI3 causes only respiratory disease. In mature cattle, infection is mild. The almost important consequence of PI3 infection in bovine respiratory disease is that information technology predisposes animals to concurrent infection with IBR or bacterial respiratory pathogens.

Bovine Respiratory Affliction Complex

Bovine respiratory illness complex is caused by a diverseness of pathogens, including the three above. Other organisms against which cattle may be vaccinated to minimize this illness complex are bovine respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV) and bacteria including Pasteurella multocida, Mannheimia haemolytica, and Histophilus (formerly Hemophilus) somnus. These pathogens collaborate with each other to cause illness. Disease is worsened in the presence of stressors including parasites, weaning, change of feed, variation in ambience temperature and humidity, and weather. Clinical signs depend on historic period of the beast, organism(s) involved, and phase of the disease. Bovine respiratory disease is closely linked with fever; information technology is i of the most common causes of fever in cattle and fever may be the first sign of disease in affected cattle. Other signs include mental dullness, lack of appetite, rapid shallow breathing, and discharge from the nose and eyes (watery to purulent to bloody). Coughing will be mild and tentative early on in the disease course and prominent ("honking") subsequently in the affliction course.

Leptospirosis

Leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease, acquired by bacteria of the genus Leptospira. In that location are many dissimilar serotypes of affliction and prevalence varies with geographic location. Serovars include hardjo-bovis, pomona, canicola, icterohaemmorhagiae, and grippotyphosa. Maintenance hosts, also called reservoir hosts, comport the bacteria and are a source of exposure to other susceptible animals. Maintenance hosts for leptospirosis include cattle, pigs, dogs, raccoons, skunks, and rodents. Animals can be infected past serovars maintained past their ain species (host-adapted infection) or by serovars maintained by other species (not-host-adapted infection). Leptospirosis tin can be transmitted either direct between animals or indirectly, through the surround. Cattle are the maintenance hosts for 50. hardo-bovis; disease in cattle with this serovar is less severe but can have a significant economic impact. Cattle infected with other seorvars, particularly L. pomona, suffer more astringent illness. Clinical signs vary with the herd's degree of resistance or immunity, the infecting serovar, and the age of the beast infected. Host-adapted infections in cattle can occur in animals of whatsoever historic period and mainly affect fertility and the renal organization. Infected cattle may shed the organism in their urine for weeks to months. Non-host-adapted infection in cattle is typically due to L. pomona and mainly affects the hemolymphatic, urinary, and reproductive systems. Acute disease is characterized past hemolytic anemia, which causes reddish urine and jaundice. Reproductive effects include infertility, stillbirths, and ballgame 1-iii months after infection. Lactating cows may endure from mastitis, with decreased product and milk that is thick and yellow.

Campylobacter

Campylobacteriosis, formerly called Vibriosis, is acquired by the bacterium Campylobacter fetus and is spread by infected bulls when they mate with susceptible cows and heifers. Once infected, a bull remains an asymptomatic carrier of the condition. Transmission is venereal; not-crabs transmission is unlikely to occur. When introduced to a herd the affliction spreads rapidly because the cows and heifers accept no immunity. Conception rates drop to around 40%. Every bit immunity develops, the affliction rate drops simply reinfection often occurs every bit amnesty wanes about a year after the initial infection. Conception rates in chronically infected herds are usually between 65 and 75%, with replacement heifers (newly introduced animals) being most severely afflicted. The infection tin can prevent implantation of a fertilized egg in the uterine lining, or more than usually, causes death of the developing embryo. When the embryo is lost, the cow goes back into heat and usually can exist rebred successfully, since she has now developed immunity. Occasionally the disease results in permanent infertility.

Clostridial Diseases

Clostridial diseases strike cattle suddenly, often causing death before any clinical signs are seen. The bacteria that cause these diseases create very long-lived spores that are constitute everywhere in the environment and can hands be picked upward past grazing cattle or enter the body through a wound. Bacteria may alive in the gastrointestinal tract and spores also may be nowadays in the tissues of good for you animals. Non all species of Clostridium crusade disease but those that do usually are fatal. Examples include:

- C. septicum – malignant edema

- C. chauvoei – blackleg

- C. perfringens types A, B, C, and D – enterotoxemia

- C. tetani – tetanus

- C. botulinum – botulism

Contributing factors are necessary to allow the bacteria to multiply and cause affliction. This may include injury or invasive procedures such as surgery, giving nascency (parturition), or puncture wounds. Diet changes, overeating, and acidosis may permit clostridial organisms in the gut to multiply and cause disease. Clinical signs differ depending on the specific organism and may include sudden expiry in evidently salubrious animals, lethargy or depression, high fever, anorexia, localized stiffness or muscle spasms, port wine colored urine, acute lameness and swelling in the hips and shoulders with a crackling audio when the peel is pressed (blackleg), or flaccid paralysis (botulism).

Brucellosis

Brucellosis is an infectious disease that spreads betwixt animal species and between animals and humans. In cattle, the bacterium involved usually is Brucella abortus. Brucellosis is highly contagious, spreading very easily betwixt cattle. The chief clinical sign is late-term abortion and the aborted calf, membranes, and fluids all contain big numbers of leaner.

*

Modest Ruminants

Modest Ruminants

Vaccination Methods

Vaccines cannot replace good management practices. When vaccinating sheep and goats, brand sure they are salubrious animals, and that the injection site is make clean and dry to forbid introducing infection with your injection. Brand sure yous have adequate treatment facilities such as a properly constructed chute or pen. When vaccinating multiple animals using an automatic syringe, verify that the correct dose is being administered. Needles should be changed every 12-20 animals (generally every pen or chute-full) and someday the needle is dull, burred, or bent. Some facilities will be part of specific disease-control programs (caprine arthritis encephalitis virus (CAE) or ovine progressive pneumonia (OPP)); in that instance, multi-dose syringes may be used but a new needle must be used for each brute. In general, xviii gauge 5/8" needles are used for developed animals and xx gauge 1/2 to five/8" needles are used for young animals. Make sure all animals are individually identified (tags, tattoos) and that there is a system for record keeping and so you know which animals received which vaccines.

To vaccinate, part the wool if necessary, raise the peel to form a tent and insert the needle into the tent opening so that the needle is almost parallel with the cervix. The site of injection is of import if the animal you are vaccinating is to be used for food. Vaccines are given then as to minimize carcass and hibernate deposition due to abscess or scar formation. Vaccines should be given subcutaneously in the neck region or in the ventral aspect of the axillary space. The meat from these regions is of low value and pelt damage in these areas easily tin be trimmed with minimal issue on value. Injection over the ribs is not optimal but it can exist used if the fauna cannot be restrained to allow you to use another location.

*

Factors to Consider in Developing a Vaccination Strategy

Which vaccines are used depends on:

- History at the individual subcontract

- Age of the sheep or goats

- Previous disease issues

- Open or airtight flock/herd condition – are animals coming and going for shows, purchases, breeding?

- Geographic region

- Soil type

- Diet and flock/herd economic science

- Withdrawal fourth dimension (refer to the label!)

To choose vaccines, consider:

- Real and high-likelihood risks

- Since all ruminants are at take chances for Clostridium perfringens type D, toxoid against this agent ideally should be used in all sheep flocks and goat herds

- Prove animals accept considerable exposure to contagious ecthyma virus (soremouth) and caseous lymphadenitis

- Open flocks have exposure to foot rot and abortion diseases

- All animals should be vaccinated with:

- CD-T vaccine – Clostridium perfringens is more commonly called enterotoxemia or overeating affliction. Type C primarily affects lambs and kids during their commencement few weeks of life. Type D (pulpy kidney illness) affects lambs and kids that are unremarkably over a calendar month of historic period, particularly those that are creep-fed or finished on concentrate diets. Clostridium tetani is the causative agent of tetanus. CD-T toxoid is the vaccine normally used to protect healthy sheep and goats against these clostridial diseases.

- Most animals should be vaccinated against Campylobacter and Chlamydophila (abortion diseases) and contagious ecthyma (soremouth).

- Some animals should be vaccinated against contagious lymphadenitis and rabies and even more rarely, confronting Eastward. coli, bluetongue virus, and Brucella ovis.

- Some people recommend use of cattle or equine vaccines in pocket-sized ruminants but they are not labeled for this use and efficacy has non been well demonstrated.

Diseases in Sheep and Goats

Diseases to be vaccinated against in sheep and goats include:

- Clostridial diseases

- Ballgame diseases in sheep

- Contagious ecthyma (soremouth, orf, scabby oral fissure or pustular dermatitis

- Caseous lymphadenitis (CLA, boils, abscesses or cheesy gland)

Clostridial Diseases

Clostridial organisms of various types are found in the soil, where they can survive for a very long fourth dimension. Most clostridial organisms as well survive naturally in the alimentary canal of healthy animals. Sheep tin can be infected with various clostridial diseases (see diseases in cattle) but the nigh common are enterotoxemia types C and D and tetanus. Enterotoxemia type C (hemorrhagic enteritis or bloody scours) is acquired by Clostridium perfringens type C and affects lambs during their kickoff few weeks of life, causing a bloody infection of the small intestine. It is ofttimes related to indigestion and is predisposed past a sudden change in feed, for instance an increase in the dam's milk supply or beginning pitter-patter feeding as lambs are being weaned. Enterotoxemia type D (overeating affliction or pulpy kidney illness) is caused by Clostridium perfringens blazon D and ordinarily strikes the largest, fastest growing lambs in the flock. It is caused by a sudden change in the feed that causes the organism, which is already present in the lamb's alimentary canal, to proliferate, causing a toxic reaction. It is most common in lambs that are on loftier concentrate rations but can also occur when lambs are nursing from dams that are heavy milkers. Information technology usually affects lambs over i calendar month of age. Sudden expiry may exist the showtime sign. Other clinical manifestations include neurologic signs, seizures, and diarrhea. Tetanus is acquired by Clostridium tetani, a soil inhabitant that is a prolific spore producer. This illness is usually related to tail docking and castration, although any wound can harbor the tetanus organism. Signs of tetanus occur from about iv days to 3 weeks or longer subsequently infection is established in a wound. The brute may have a stiff gait, lockjaw can develop, and the third eyelid may protrude across the center. The animal usually volition get down with all four legs held out direct and potent and the head fatigued back. Convulsions may occur.

Abortion Diseases

Ewes or does that lose their lambs early in pregnancy may not render to heat because they are seasonal breeders, and so may non be bred back that season. This is a significant loss for the producer both because of decreased lamb ingather and because those dams volition not lactate that season. Pregnancy likewise may be lost late in gestation or weak or deformed lambs may exist born. For many diseases causing abortion in small ruminants, at that place is no vaccine in the United States (for instance, Q fever, toxoplasmosis, Border disease). In the The states, the most common causes of abortion in ewes are Chlamydia / Chlamydophila (enzootic abortion) and Campylobacter. Enzootic abortion is transmitted from aborting dams to other females in the flock. Ewe lambs are the most susceptible on farms where the organism is present. Abortion usually is seen late in pregnancy or lambs may be built-in that dice presently after nativity. Campylobacteriosis (formerly chosen Vibriosis) causes ballgame late in pregnancy or nativity of stillborn or weak lambs. Infecting organisms are Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter fetus. Ewes are infected orally and the incubation time from ingestion to abortion is just 2 weeks.

Contagious Ecthyma (soremouth, orf, scabby mouth, or pustular dermatitis)

Soremouth is the well-nigh common pare affliction affecting sheep and goats. It is a highly contagious viral infection that also can produce painful infections in humans. The virus causes scab formation on the peel, usually around the rima oris, nostrils, eyes, mammary glands, and vulva. It outset appears as tiny red nodules, usually at the junctions of the lips.

Caseous Lymphadenitis (CLA, boils, abscesses, or cheesy gland)

Caseous lymphadenitis is an infectious, contagious disease that primarily infects the lymphatic organization, though other organs can exist affected. It is caused past Corynebacterium pseudotuberculosis. Infection results in abscess formation in the lymph nodes that when cut or ruptured, discharge pus containing the bacteria in the environs. When the infection spreads internally, affected animals slowly lose weight and eventually go emaciated.

Vaccines for Disease in Sheep and Goats

Specific vaccines that are bachelor are:

- CD-T (Clostridium perfringens types C and D and tetanus toxoid)

- Abortion vaccines

- Contagious ecthyma (soremouth, orf)

- Caseous lymphadenitis (CLA)

- Rabies

CD-T (Clostridium perfringens types C and D and tetanus toxoid)

Protection against blazon C is needed by nursing lambs and kids on all farms, regardless of management practices. Maternal antibodies will be nowadays in colostrum if the ewe/doe was vaccinated in the ii-4 weeks prior to parturition. This passive immunity lasts in the lamb/kid for their showtime l-threescore days of life. Protection against type D is needed in lambs/kids fed grain or lush forage (whatsoever high-carbohydrate diet). Information technology is associated with product of a toxin that is acutely fatal in fast-growing lambs. Tetanus toxoid is included in this product. Ewes and does should be vaccinated 8 weeks prior to the outset time they give birth, and boostered at 2-4 weeks prior to parturition. Previously vaccinated ewes and does just require the vaccination 2-4 weeks prior to parturition. Offspring from vaccinated dams are vaccinated at weaning and once more 3-4 weeks afterward. Offspring from unvaccinated dams are vaccinated as newborns (may have systemic reaction, can exist treated with epinephrine) and are boostered at 3-iv weeks of age and again at weaning. All animals, including males, should be boostered at least annually; some goats may but maintain protective antibiotic titers for half dozen months after vaccination.

Abortion Vaccines

In general, do not vaccinate if in that location are no problems on the farm or if animals are determined to be at low chance. Risk is associated with having an open flock, with animal traffic on and off the farm, with free-roaming wild fauna, feeding on the ground, or with a history of abortions in the flock. Diagnosis for abortion problems is difficult and for many diseases causing abortion in small ruminants, there is no vaccine in the United states of america (for example, Q fever, toxoplasmosis, Border illness).

- Chlamydia / Chlamydophila (enzootic abortion) vaccine may not be effective confronting all strains causing abortions and regional variations in protection may be. The label states that the vaccine should be administered threescore days prior to convenance with a booster in 30 days.

- Campylobacter (formerly called Vibrio) vaccination induces immunity for only 4-5 months. The characterization states that the first dose of vaccine should be given 2 weeks prior to convenance and that it should be boostered 2-three months subsequently. In the face of an "abortion storm," where many abortions are occurring in the flock due to this organism, revaccination of all animals may reduce losses.

Contagious Ecthyma (soremouth, orf)

This is a live virus vaccine that will introduce a mild infection. This vaccine should only be used if this illness is present in the flock. The vaccine is given percutaneously; an area of peel in a wool-less region (inside the thigh or ear, or nether the tail) is scarified in the form of an X securely plenty to cause inflammation but non so securely as to cause bleeding. The vaccine is brushed on. The vaccinated area will scab over and does contain live virus that volition be infective even after falling off the sheep. Vaccination under the tail is preferred to that inside the thigh, every bit vaccination on the medial thigh region may cause irritation and scabbing over the mammary glands and teats. This is a zoonotic disease then people should wear gloves and practise caution when handling the vaccine or sheep, or picking upward scabs. On farms that have a trouble with this disorder, each new lamb and kid crop should be vaccinated. Lambs moving into feedlots should be vaccinated at to the lowest degree 14 days earlier shipment. Do non use this vaccine on farms that do not already have this disorder.

Caseous Lymphadenitis (CLA)

This may exist a stand-alone vaccine or combined with CD-T vaccine. Vaccination decreases severity of disease but does non prevent disease. The vaccine should not be used in flocks or herds unless they have been exposed or contain afflicted individuals.

Rabies

This is a killed vaccine. Several products are available for sheep. No products are specifically labeled for goats merely in that location is a recommendation in some situations that publicly displayed goats will be vaccinated. For example, goats take to a show that volition be housed in a pen probably will not be vaccinated for rabies, while goats at a petting zoo that are purposefully brought to that site to collaborate with people will exist vaccinated for rabies. Animals are vaccinated when greater than 3 months of age and then annually.

*

SWINE

SWINE

Vaccination is a common preventive medicine exercise on commercial swine farms. Vaccination protocols for swine typically focus upon preventing diseases of the reproductive, respiratory, and gastrointestinal tracts, and preventing multi-systemic disease. Vaccines may be practical to the reproductive herd (sows and boars), replacement females (gilts), or growing pigs, depending on when the affliction challenge is expected.

- Commercial (manufactured and sold by pharmaceutical companies)

- Autogenous (typically manufactured past a licensed laboratory from organisms isolated from the farm of concern)

- On Farm – Typically includes other, less controlled, methods that stimulate immunity such as oral feeding of infectious organisms ('biofeedback') or inoculation with serum from viremic animals (serum inoculation)

Routes of assistants for swine vaccines typically include IM or oral (per os = PO). Multivalent vaccines (those containing multiple organisms) are usually created to subtract the stress, labor, and nutrient safe issues associated with multiple injections. Swine farm clientele look that veterinarians will consider the costs and benefits associated with the vaccination protocols they recommend.

- Use a spot on the neck just behind and below the ear, just in forepart of the shoulder. Practise not employ a needle to inject in the ham or loin. There may be some haemorrhage and bruising of the musculus followed past scarring. This scar can stay in the muscle for the life of the pigs and be a blemish in the cutting of meat. This standard applies to sows as well as market hogs. While sows may not exist going to market presently, they are at greater gamble for blemishes considering of the repeated injections they typically receive over their productive life in the form of vaccinations and farrowing medications.

- Use the proper size and length of needle to ensure the medication is deposited in the muscle, not in other tissues.

| Estimate OF NEEDLE | LENGTH OF NEEDLE (INCHES) | |

| Baby Pigs | eighteen or 20 | ½ or ⅝ |

| Plant nursery Pigs | 16 or xviii | ⅝ or ¾ |

| Finisher Pigs | 16 | 1 |

| Breeding Stock | 14, 15 or 16 | ane or 1½ |

Diseases in Swine

Diseases to vaccinate confronting in swine include:

- Leptospirosis

- Erysipelas

- Porcine parvovirus (PPV)

- Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS)

- Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae

- Flu

- Escherichia coli

- Rotavirus

- Porcine Proliferative Enteritis (PPE)

- Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2)

- Meningitis

Leptospirosis

As in cattle, leptospirosis is a zoonotic disease, caused by bacteria of the genus Leptospira. In that location are many different serotypes of illness and prevalence varies with geographic location. Worldwide, pigs are the maintenance hosts for pomona, tarassovi, bratislava, and muenchen. Pomona causes important reproductive problems in breeding sows, spreading slowly through the herd. The skunk is a reservoir host. Once the organism is introduced into a herd, the pigs go permanent carriers with infection of the kidneys and intermittent excretion of the organism into the urine. Piglets rarely are infected. The most common manifestation is chronic low-class illness in sows, with abortions, stillbirths, and birth of weak piglets.

Erysipelas

Swine erysipelas is caused by a bacterium, Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae, that is found on most if not all pig farms. Up to half of the animals on a subcontract may conduct it in their tonsils. It is excreted in saliva, feces, and urine, and then is common in the environment. Information technology is also found in many other species, including birds, and can survive for long periods in the environment. The bacterium alone may crusade illness only clinical illness is more than common if there is concurrent infection with viral diseases such every bit porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome (PRRS) virus and flu. Affliction is relatively uncommon in pigs nether 8-12 weeks of age due to protection provided past maternal antibodies from colostrum. The most susceptible animals are growing pigs, not-vaccinated gilts, and young sows. Infected sows may show acute decease in plain salubrious animals, fever, abortion, stillbirths, birth of mummified piglets, raised areas in the skin ("diamonds") that turn scarlet and and then black, or articulation stiffness. Infertility may be a presenting business concern on a farm. Infected boars with high fevers have transient decrease in semen quality, reflected equally sows non getting pregnant or having smaller litters. Infected growing pigs may show acute expiry, fever, and the feature peel lesion described higher up.

Porcine Parvovirus (PPV)

PPV is the well-nigh common and important crusade of infectious infertility in pigs. Porcine parvovirus multiplies unremarkably in the intestine of the grunter without causing clinical signs. It is worldwide in its distribution. PPV can persist in the environment for many months and is resistant to most disinfectants. Infected sows prove merely reproductive signs of disease. Parvovirus is associated with lack of conception, nativity of mummified or stillborn pigs, and nascency of alive pigs with low nascency weight. Sporadic disease is seen in individual females that are infected for the get-go fourth dimension; for this reason, affliction usually is seen in gilts. Once a pig is exposed, it has lifelong immunity. Reproductive bug in a herd announced about every 3-4 years if vaccination is not practiced.

Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome (PRRS)

This is a adequately new disease; information technology has only been recognized in the United States since the mid-1980s and was but identified as being acquired by an arterivirus in 1991. The virus has an affinity for macrophages, especially those in the lung. Up to 40% of macrophages are destroyed in a given fauna, making it susceptible to other diseases. When introduced into a new herd, 90% of breeding sows volition exist seropositive inside four-5 months. Grower pigs shed virus for months; adult pigs shed virus for periods of time as short as two weeks. Nasal secretions, saliva, feces, and urine may contain virus. The virus tin be airborne for up to 2 miles and tin be carried between pigs and on fomites (inanimate objects) including boots, equipment, and trucks. The virus also may be carried past flies and mosquitoes. The clinical picture varies tremendously from i herd to another. Equally a guide, for every three herds that are exposed to PRRS for the first time, one will prove no recognizable affliction, the 2d will bear witness mild disease, and the 3rd will show moderate to severe disease. The reasons for this are not clearly understood. Clinical signs in sows include inappetance; fever; abortions; early farrowing with birth of mummified, stillborn, or weak pigs; prolonged return to rut after weaning of piglets; coughing; lack of milk and mastitis; lethargy; and cyanosis (blue discoloration) of the ears. This is the astute phase of the disease. Long-term, reproductive efficiency in herds in which the infection has become enzootic are associated with 10-15% reduction in farrowing rate, increased stillbirths, increased number of abortions, and inappetance in sows at farrowing. Infected piglets may show diarrhea and increase in other respiratory infections. Infected weaning and growing pigs may bear witness other infections secondary to PRRS infection with a variety of clinical signs and mortality charge per unit every bit high as 12-15%.

Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae

This is ane of the nearly important contributors to respiratory disease in pigs. The organism amercement the cilia and epithelia of the airways of the lower respiratory tract, permitting infection with other organisms, for case PRRS virus. Mycoplasma is transmitted via direct contact with infected pigs. Pigs older than half dozen weeks are mainly those affected. Clinical signs include a non-productive cough, rough pilus coat, and reduced growth rate and feed efficiency. With secondary bacterial infection, signs are more than astringent and include labored breathing, a harsher cough, fever, and prostration.

Flu

Influenza viruses are the crusade of outbreaks of acute respiratory disease. Influenza A viruses infect a wide range of avian and mammalian species, with the latter grouping including humans, pigs, horses, and aquatic mammals. Blazon A viruses are known for their power to modify their antigenic structure and create new strains. The type A viruses are further divided into serotypes, based on the antigenic nature of their surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (H) and neuraminidase (North). Swine influenza in big herds may become endemic with intermittent bouts of disease and infertility. Dissimilar influenza strains may sequentially infect the herd. Immunity to influenza viruses is often brusque-lived (six months). Outbreaks are seen throughout the year. Piglets generally are protected by maternal antibodies they receive in colostrum. Sows may show pregnancy loss secondary to fever and coughing. Weaner and grower pigs with acute illness classically are fine ane twenty-four hours and and so lying prostrate and animate heavily the next.

Escherichia coli

Diarrhea is the nigh common and important illness of piglets. In a well-managed herd, there should be fewer than three% of litters at any time requiring handling for diarrhea and piglet mortality from diarrhea should be less than 0.5%. At birth, the gastrointestinal tract is microbiologically sterile. Organisms begin to colonize the tract quickly after birth, amid them potentially pathogenic strains of E. coli. Ingestion of colostrum and later, of milk containing IgA, is vital for creation of immunity inside the intestinal tract. If as well many bacteria are present or if there are stressors nowadays such equally chilling or concurrent infection, piglets will succumb to disease. Periods of greatest take a chance are before v days of age and between 7 and fourteen days of age. Weaning is another risk, as loss of sow's milk and the IgA it contains allows the bacteria to attach to the villi of the small intestines. Signs may include acute death, dehydration, and sticky carrion around the rectum and tail with an accompanying characteristic sour smell.

Rotavirus

This virus is widespread in pig populations, with virtually 100% seroconversion in adult stock. It is resistant to ecology changes and many disinfectants and so persists for long periods of fourth dimension in the surroundings. Piglets are initially protected from maternal antibodies in colostrum but go susceptible to infection by nigh iii-6 weeks of age. Exposure does non necessarily upshot in disease; it is estimated that only 10-15% of diarrheas in pigs are due to primary rotavirus infection. The virus destroys the intestinal villi, preventing fluid uptake and causing watery diarrhea.

Porcine Proliferative Enteritis (PPE)

This is a illness characterized histologically by inflammation, ulceration, and hemorrhage in the intestinal tract. The causative organism, Lawsonia intracellularis, is a unique obligate intracellular organism related to anaerobic bacteria. Clinical affliction is characterized as an acute form common in young adults and a chronic or necrotic form in grower pigs. Carrier animals shed the organism in their carrion and susceptible pigs are exposed through the fecal-oral road. Carrier sows may infect nursing pigs as early every bit half dozen days of historic period. Pigs present with pallor, weakness, and rapid death. Subacute to chronic cases occur more frequently in grower pigs, which show desultory diarrhea, wasting, and variation in growth rate.

Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2)

This is a widespread virus and essentially all pig herds are infected. Yet, very few take PCV2-associated illness which can include a variety of systemic disorders including clinical signs of wasting, pneumonia, enteritis, and reproductive failure. The hallmark of PCV2 infection is depletion or inflammation of lymphoid tissue. In many cases, PCV2 infection requires a trigger such as concurrent infection (PRRS virus, Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae) or other stressors.

Meningitis

Hemophilus parasuis and Streptococcus suis are ii organisms associated with inflammation of the meninges in pigs. Signs of meningitis in piglets and weaned pigs include rapid onset of recumbency, shivering, nystagmus (shaking of the eyeballs), paddling, and convulsions. In older pigs (growers and adults), muscle trembling, nystagmus, and incoordination are more common clinical signs.

Vaccines for Disease in Swine

Vaccination for Reproductive Disease

Common vaccinations include:

- Leptospirosis-Erysipelas-Parvovirus combination vaccine

- Each of these components may exist administered every bit individual vaccinations likewise

- Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRS) vaccine

- Modified live virus vaccine typically thought to exist most effective

Common uses are:

- Typically administered twice prior to the first breeding of gilts and one time before subsequent gestation periods in reproductive herd (sows and boars)

Vaccination for Respiratory Disease

Common vaccinations include:

- Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae vaccine

- Single dose and 2 dose versions exist

- Swine Flu virus vaccine

- Ordinarily include H1N1 and H3N2 components

- Porcine Reproductive and Respiratory Syndrome virus (PRRS) vaccine

Common uses are:

- Routine vaccinations in reproductive herds to maintain respiratory affliction stability

- Acclimation of affliction-negative replacement females every bit they enter disease-positive herds

- Growing pigs at weaning or during the plant nursery phase to forestall significant respiratory disease during the finisher phase

Vaccination for Gastrointestinal Disease

Common vaccinations include:

- Escherichia coli vaccine

- Multiple strains typically included in the vaccine

- Rotavirus vaccine

- Modified live virus, only one type included in commercial vaccine

- Lawsonia intracellularis vaccine

- A modified live vaccine that requires storage at -70°C and it administered orally following thawing and dilution

Common uses are:

- Escherichia coli and Rotavirus vaccines commonly used prior to farrowing to prevent neonatal scours in suckling piglets

- Lawsonia intracellularis vaccines administered in late nursery or early finisher (9-12 weeks of historic period) to forestall ileitis in finisher pigs OR for the acclimation of replacement females into breeding herds

Vaccination for Multi-Systemic Affliction

Mutual vaccinations include:

- Porcine Circovirus Type 2 (PCV2) vaccine

- Currently the virtually mutual vaccine used in swine

- Considered to be highly constructive in preventing a devastating disease syndrome

- Show that it provides constructive protection in both single and two dose programs.

- Hemophilus parasuis vaccine

- Typically includes multiple serotypes that provide cantankerous protection for other serotypes

- Erysipelas rhusiopathiae vaccine

- May be delivered IM or PO

- Streptococcus suis vaccine

- Efficacy is questionable

- Normally produced as an autogenous vaccine

Common uses are:

- These vaccines are often manufactured in combination type products with respiratory specific vaccines to prevent disease in replacement females or growing pigs.

Source: https://pressbooks.umn.edu/vetprevmed/chapter/chapter-4-vaccines-and-vaccinations-production/

Posted by: anthonypernihiststo.blogspot.com

0 Response to "When Did Farm Animals Start Getting Vaccinated"

Post a Comment